International Women's Day

March 8, known as International Women's Day (or in Germany also known as “Feminist Struggle Day”) , has been a symbol of the achievements of international feminist movements for over a century. Its origins date back to the socialist workers' movements of the early 20th century. In 1910, the German socialist politician and women's rights activist Clara Zetkin proposed the introduction of an International Women's Day at the Second International Socialist Women's Conference in Copenhagen (Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund, 2021). This first took place in 1911 and was officially recognized by the United Nations as an international day of action in 1977 (United Nations, n.d.).

On the continued relevance of feminist social analysis

Although legal equality is largely enshrined in law in Germany and many other countries, it is increasingly claimed in public debates that feminism is outdated or no longer necessary. However, an empirical analysis of key social indicators shows that significant structural inequalities persist. In this context, feminism is not just a trendy topic, but a gender-equitable perspective on power relations, institutional structures and social inequalities.

Economic inequality

The gender pay gap

The gender pay gap is a key indicator of gender-specific inequality. According to the Federal Statistical Office (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2025), the gender pay gap in Germany was 16% in 2025. Women earned an average of 22.81 euros gross per hour, men 27.05 euros.

The causes include the horizontal segregation of the labor market, i.e. the increased distribution of women in low-paid sectors, as well as vertical segregation, i.e. the underrepresentation in management positions (Antidiskriminierungsstelle des Bundes, 2026; Koebe et al., 2020). In addition, there are interruptions in employment that affect wages in connection with care work and family planning. The long-term consequences are particularly evident in old-age provision. Women are significantly more likely to be affected by poverty in old age than men (Schlapeit-Beck, 2022). Economic inequality is therefore not just the result of individual career decisions, but an expression of structural conditions. And if these structural differences, such as industry, working hours and qualifications, are deducted from the gender pay gap, an unexplained residual difference of around 6% remains (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2025).

The gender care gap

In addition to paid work, unpaid care work plays a central role in social equality between the sexes. The so-called gender care gap describes the gender-specific difference in the amount of time spent on unpaid care work. On average, women in Germany perform around 44% more unpaid care work than men (BMFSFJ, 2025; DIW, 2022).

This unequal distribution has a direct impact on the choice of working time model and therefore on employment. Women are more likely to work part-time or interrupt their employment due to family/social obligations. The gender care gap therefore acts as a mechanism for reproducing economic inequality. The longer periods of unpaid work result in structural discrimination. Although political measures such as the expansion of childcare or parental allowance regulations have brought about progress, there has been no structural equalization to date (BMFSFJ, 2018).

Unequal distribution of power

Representation of women in business and politics

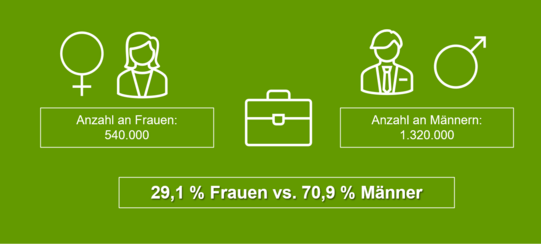

There is also a clear underrepresentation of women in management positions. The proportion of women in management positions was 29.1% in 2024. In absolute figures, this means that 1.32 million men held a management position in Germany in 2024, compared to only 540,000 women. These figures have hardly changed in the last ten years (Statistisches Bundesamt, 2025b). Despite statutory quotas, senior management positions in particular remain male-dominated.

In the German Bundestag, the proportion of women is currently 32.4% and has therefore fallen compared to the previous Bundestag. Even if the proportion varies between the parties, the average value shows a clear underrepresentation of women in the political context (Deutscher Bundestag, 2025). This means that equal democratic representation has not been achieved. Political science analyses point to structural hurdles in internal party selection processes as well as gender-specific role expectations, which become an obstacle for women. However, democratic equality presupposes that social diversity is adequately represented in political decision-making structures, which is currently not the case in Germany (Höhne, 2020).

Gender-based violence and femicides

Gender-based violence and femicides are also a relevant factor in structural power relations between the sexes in Germany. According to the Federal Criminal Police Office (Bundeskriminalamt, 2024), over 250,000 cases of domestic violence were registered in 2023, around 70% of those affected were female. This represents an increase of 6.5% within three years. These cases also include acts of intimate partner violence. In 2024, around 167,000 cases were registered, with almost 80% of those affected being female. Of the suspects, 77.6% are men. In addition, 155 women were killed by their partner or ex-partner in the context of intimate partner violence (Bundeskriminalamt, 2024). These figures only represent the crimes that were reported to the police. The number of cases that were not reported due to factors such as fear, shame, dependency, etc. are not known.

In the gender policy debate, these homicides are referred to as "femicides", i.e. murders of women because of their gender or in the context of patriarchal claims to ownership and control (bpb, 2022). The high number of cases makes it clear that gender-specific violence is not an isolated criminal phenomenon, but an expression of structural power relations.

International feminist struggles: Global dimensions of inequality

Feminist struggles are not limited to national contexts, but are part of international movements. Feminist initiatives around the world are mobilizing against gender-based violence, for reproductive rights, for equal access to education and for economic independence. International women's strikes, protests against restrictive abortion laws and movements against authoritarian gender policies illustrate the global dimension of gender inequality.

UN Women (2023) points out that women worldwide are disproportionately affected by poverty, are more likely to work in precarious employment and suffer particularly badly from the effects of crises such as pandemics, armed conflicts or climate change. Gender equality is therefore explicitly anchored as a goal of sustainable development in the 2030 Agenda (United Nations, 2015). The 5th Sustainable Development Goal ("Achieve gender equality and empower all women and girls" (United Nations, 2015)) shows that gender equality is not just a human rights issue, but a prerequisite for sustainable development, democratic stability and economic growth.

International feminist movements are thus pursuing the goal of achieving legal and de facto equality, combating violence, ensuring reproductive self-determination and making intersectional forms of discrimination visible. The global nature of these struggles shows that gender justice cannot be achieved in isolation at a national level, but must be considered in an international context.

The relevance of feminism today

The empirical data makes it clear that formal equality cannot be equated with real equality. The persistent gender pay gap, the unequal distribution of care work, the underrepresentation in leadership and decision-making positions and the high number of gender-specific violent crimes against women are evidence of structural inequalities and power relations to the detriment of the female population. Against this backdrop, feminism remains a necessary social and political practice in 2026. The Feminist Day of Struggle is not merely a symbolic commemoration, but an opportunity to critically assess existing power relations and formulate future equality policies.

Status: March 2026

Author: Mathuraa Vivekananthan

Events in Dortmund (and the surrounding area)

International Women's Day (Equal Opportunities Office of the City of Dortmund)

When? Sunday, March 8 from 10 a.m. Breakfast together; program starts at 11 a.m.

Where? City Hall, Friedensplatz

Participation free of charge!

Program: Insight into the year2025 from the perspective of the Equal Opportunities Office Dortmund, consideration of the current challenges and an outlook on the work in the near future. Furthermore, award ceremony of the Dr. Edith Peritz Prize and opportunity to participate in workshops. Further information.

International Women's Day: Girls & Gods

Where? Roxy Lichtspielhaus Dortmund

When? Sunday, March 08 from 17:30 to 19:15

Cost: from 8,00 € to 9,00 €

Demonstration "FAUCHEN STATT FÜGEN - WE ARE STILL LIVING FEMINISM"

When? On 08.03.2026 from 3 pm

Where? Buddenbergplatz, Bochum (rear exit of the main station)

Sources (in German)

Antidiskriminierungsstelle des Bundes (2026). 21. Segregation, horizontal und vertikal. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

Bundeskriminalamt (BKA) (2024). Häusliche Gewalt im Jahr 2023 um 6,5 Prozent gestiegen. 70 Prozent der Opfer sind weiblich / Bundesministerinnen Faeser und Paus stellen aktuelles BKA-Lagebild vor. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

Bundesministerium für Bildung, Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (BMFSFJ) (2028). Zweiter Gleichstellungsbericht. Erwerbs- und Sorgearbeit gemeinsam neu gestalten. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

Bundesministerium für Familie, Senioren, Frauen und Jugend (BMFSFJ) (2025). Gender Care Gap – Ein Indikator für Gleichstellung. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

Höhne, B. (2020). Frauen in Parteien und Parlamenten. Innerparteiliche Hürden und Ansätze für Gleichstellungspolitik. Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung - bpb. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

Bundeszentrale für politische Bildung (bpb) (2025). Femizide und Gewalt gegen Frauen. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

Deutscher Bundestag (2025): Abgeordneten-Statistik: Der neue Bundestag in Zahlen. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

Deutsche Gewerkschaftsbund (DGB) (o. J.): Der Weltfrauentag. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

Deutsches Institut für Wirtschaftsforschung e.V. (2024). Gender Care Gap. DIW.

Koebe, J., Samtleben, C., Schrenker, A., & Zucco, A. (2020). Systemrelevant und dennoch kaum anerkannt: Das Lohn- und Prestigeniveau unverzichtbarer Berufe in Zeiten von Corona. DIW Berlin. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

Schlapeit-Beck, D. (2022). Altersarmut ist weiblich. zwd Politikmagazin. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2025a). Gender Pay Gap 2025 unverändert bei 16 %. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

Statistisches Bundesamt. (2025b). Deutschland unter EU-Durchschnitt: Weniger als jede dritte Führungskraft ist weiblich. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

United Nations (UN) (o. J.). History of Women´s Day. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

United Nations. (2015). Transforming our world: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.

United Nations Women (2023): Progress on the Sustainable Development Goals: The gender snapshot 2023. Last accessed: 06.03.2026.